Quit Fooling Around: Serious IP Issues for Mobile and Video Game Companies

While the business of mobile and video gaming may be, well . . . just fun and games – every professional in this ever growing industry must be aware of the IP boundaries and protections of their own – and their competitor’s — games. Crossing the line could cost millions.

SLG is pleased to highlight these important issues through recent legal victories and defeats of well known players in the game business, organized in three (3) areas: (1) copyrights, (2) trademarks, and (3) trade dress. We would be happy to discuss this further at your convenience.

- Copyright Protection for Games.

Copyright protection for mobile and online games is expansive and encompasses the source code; in-game sounds and music; characters, creatures, animals, in-game artwork, concept artwork; icon artwork; visual depictions of locations and landmarks, as well as names, titles, and descriptions, among other things. These copyright protections are exemplified in the following four (4) case examples.

a. Registering Source Code Provides Strong Protection for Game and UI Against Competitors that Engage the Same Third Party Developers.

Bethesda Softworks LLC[1] (“Bethesda”), a giant in the gaming industry, recently stopped Warner Bros. cold from infringing the software copyright to Bethesda’s highly successful mobile game Fallout Shelter. In developing Fallout Shelter, Bethesda engaged a Canadian firm, Behaviour Interactive, Inc. (“Behaviour”), to develop the game, including the software. Bethesda wisely registered the software for Fallout Shelter with the U.S. Copyright Office.

In light of Fallout Shelter ‘s success, Warner Bros. hired Behaviour – the same game developer — to build a similar game called “Westworld.” In “developing” this game for Warner Bros., Behaviour unlawfully used Bethesda’s copyrighted code and trade secrets.[2] In fact, “Behaviour’s use of the computer code owned by Bethesda to develop Westworld even included the very same ‘bugs’ or defects present in the Fallout Shelter code.”[3] Thanks to the software copyright registration, Bethesda forced Warner Bros. to pull the copycat game from the app stores and to haul Behaviour, a Canadian company, into a U.S. federal court. The case was ultimately settled.

b. Registering Game Source Code Provides Strong Protection Against Employee Theft.

In one of the most egregious cases of copyright theft and infringement in recent memory, the copyright registration of game source code (and the games themselves) led to an unprecedented jury verdict of Five Hundred Million Dollar ($500,000,000) for famed game developer, Zenimax Media Inc. (“Zenimax”), developer of Doom, one of the most popular games of all time.

This case represents the biggest nightmare for every game company. In 2012, the early days of virtual reality (VR) headset development, the founder of Oculus VR, LLC (“Oculus”), Palmer Lucky, reached out to Zenimax to help develop software to enable integration of the headset prototype called “Rift”.[4] Oculus had not even been incorporated at that time.

Zenimax had been working on such software since the 1990’s and assigned its top developer to work with Oculus. Zenimax and Oculus signed an NDA, but never signed any further agreements. Zenimax thought it would help a startup that could ultimately benefit Zenimax and never charged Oculus for its work; and received no compensation whatsoever.

Rather than benefiting from this good faith cooperation, Zenimax’s lead developer stole software and hardware from Zenimax, and joined Oculus, which was later acquired by Facebook for $2 billion – despite Facebook’s knowledge of the stolen code. The software copyright registration absolutely saved the day for Zenimax.

c. Copyright Registration Protects Game Characters and Game Elements.

In Blizzard Entm’t, Inc. v. Joyfun Inc. Co., [5] Blizzard Entertainment, Inc. (“Blizzard”) used its copyright registrations in the games World of Warcraft, Heroes of the Storm, Starcraft, Hearthstone, among others, to prevent the sale by Joyfun Inc Co., a Hong Kong company (“Joyfun”), of its mimicked copycat mobile game, Glorious Saga.

Joyfun’s copying was extreme and included visual depictions of Blizzard’s

characters, creatures, animals, and monsters; Blizzard’s in-game artwork or concept artwork; Blizzard’s in-game icon artwork; visual depictions of locations and landmarks which appear in Blizzard’s games; and Blizzard’s sound and/or music files. In addition, Joyfun used Blizzard’s descriptions of in-game content using the same names, titles, or descriptions.[6]

The case was settled, but not before the judge issued a permanent injunction against Joyfun, preventing Joyfun’s mobile game from being sold, advertised, or made available for download in the U.S.

d. Game Music and Soundtracks Warrant Copyright Protection

Copyrights also provide protection to game music and sound effects used in these games. In a case filed in September of 2019,[7] video game maker Gearbox Software L.L.C. (“Gearbox”), was sued for using infringing music in its game titled Duke Nukem 3D World Tour.

In connection with a prior version of the game released in 1996 called Duke Nukem 3D, famed games music composer Bobby Prince wrote 16 songs which he copyrighted and then licensed for use solely in that prior version of the game.

In 2016 – ten (10) years after the first release — Gearbox released a new version of the game and included the same music as the prior version. Gearbox failed to obtain the rights to use the music from the composer – and shortsightedly refused to negotiate a rights agreement with the composer before releasing the game. The case was settled soon after it was filed – undoubtedly to the benefit of Prince.

- Trademark Protection for Games.

Trademark protection for mobile and online games – both for registered trademarks and common law trademarks — is also quite broad and is generally used to protect titles of games and the game developer’s corporate name. The below two (2) cases highlight the importance of pre-launch game naming diligence and the devastating consequences that could arise from failing to appreciate the strength of trademarks.

a. Enforcement of Trademark Prevents Release of Video Game.

In Garcia v. Gravity Interactive, Inc.,[8] the owner of the registered trademark, “DRAGONICA,” used in connection with a band name and its music, blocked the release of an online game bearing the name “DRAGONICA Online.” The case was quickly settled and the infringing game developer changed the name of its game to Dragon Saga.

b. Common-law Trademark Trumps Registered Mobile Game Trademark.

Even common law trademarks can have teeth under the appropriate circumstances. In a recent case,[9] Ren Ventures Ltd (“Ren Ventures”) created a mobile card game named Sabacc, based on the fictional card game “Sabacc” from the Star Wars movies. Prior to releasing the game, Ren Ventures applied for, and actually received, registration of the trademark “Sabacc” with the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

Despite the existence of Ren Ventures’ registered trademark, Lucasfilm Ltd. (“Lucasfilm”), the owner of the Star Wars intellectual property portfolio, charged Ren Ventures with infringement on the grounds that Lucasfilm had common law trademark rights in “Sabacc” based upon its prior use of the mark – despite Lucasfilm’s failure to register the trademark.

After the court acknowledged the priority of the Lucasfilm common law rights to the registered trademark, the Ren Ventures trademark was cancelled, and the case was settled.

- Trade Dress Protection for Games.

Trade dress is another important layer of protection afforded to game developers to prevent or stop copycats from appropriating the look and feel of mobile and video games. The Lanham Act, the same U.S. federal law that protects trademarks, also contains a special provision giving protection to trade dress.[10] The two (2) cases below illustrate the scope of trade dress protection for games.

a. The Tetris v. Xio Case.

Trade dress saved the day in a case concerning the iconic Tetris computer game, Tetris Holding, LLC v. Xio Interactive, Inc. [11]

In this case, Xio Interactive, Inc. (“Xio”) created a mobile game “inspired” by the classic game, Tetris, developed by Tetris Holding, LLC (“Tetris”). According to the court, Tetris developed trade dress protection in the look and feel, layout, color schemes, and the collection of other visual design elements that gave the game its signature look.

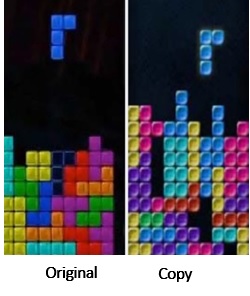

Specifically, Tetris’s trade dress protection extended to “the brightly-colored Tetriminos, which are formed by four equally-sized, delineated blocks, and the long vertical rectangle playfield, which is higher than wide.”[12] The original and copied trade dress is reproduced below:

Following these important findings, the court issued a permanent injunction against Xio, the case was settled, and the defendant took the game down from the mobile app store.

b. The Atari (Pong) v. Target Case.

Trade dress, when coupled with a valid trademark, can provide much needed protection from infringement. In a recently settled case,[13] Atari Interactive, Inc. (“Atari”), sued famed U.S. retailer, Target Corporation, for trademark and trade dress infringement[14] of the first mass market video games, Pong,[15] launched in 1972.

Despite the notoriety of Pong, Target decided to launch an in-store interactive customer display in numerous Target locations, which appropriated the look and feel, appearance, and mechanics of Pong. The side by side comparison could not be any clearer:

In a critical lapse of judgment by Target, rather than heeding the warning of a cease and desist letter issued by Atari, Target openly refused to cease its infringement, in total defiance of Atari’s intellectual property rights. The case was heavily litigated for a period of ten (10) months – undoubtedly costing both parties hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The case was ultimately settled, and Target’s Foot Pong game was removed from stores. Hence, Atari’s rights in Pong prevailed.

SLG has extensive experience advising clients on copyright, trademark, trade dress, misappropriation, and related intellectual property matters. We would be happy to assist your company navigate the minefield of IP in the gaming context. For more information, please contact SLG at info@shelgroup.com.

[1] The case settled on November 12, 2020.

[2] Copyright infringement was also alleged by Atari.

[3] See Atari Interactive, Inc. v. Target Corporation, Case No. 0:20-cv-00054-PJS-BRT (D. Minn. Jan. 6, 2020).

[4] See Bethesda Softworks LLC v. Behaviour Interactive, Inc., 8:18-cv-01846 (D. Md. 2018).

[5] See Bethesda Complaint (Dkt. # 1) at ¶ 6.

[6] Id. at ¶ 8.

[7] See Zenimax Media Inc. v. Oculus VR, LLC, Civil Action No. 3:14-CV-1849-K, 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 107420 (N.D. Tex. June 27, 2018).

[8] See Blizzard Entm’t, Inc. v. Joyfun Inc. Co., No. SACV 19-1582 JVS (DFMx), 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 74722 (C.D. Cal. Feb. 7, 2020).

[9] See Amended Complaint (Dkt. # 32) at ¶ 55, Case 8:19-cv-01582-JVS-DFM, (Nov. 7, 2019).

[10] See Prince v. Gearbox Software, LLC et al., No. 3:19-cv-00380-JPM-HBG, 2019 (E.D. Tenn. Sept. 27, 2019).

[11] See Garcia v. Gravity Interactive, Inc., No. 10-62162-Civ, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 198334 (S.D. Fla. Jan. 17, 2012).

[12] See Lucasfilm Ltd. LLC v. Ren Ventures Ltd., No. 17-cv-07249-RS, 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 97238 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 24, 2018).

[13] See 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(3); (c)(4).

[14] 863 F. Supp. 2d 394 (D.N.J. 2012).

[15] Id. at 415.